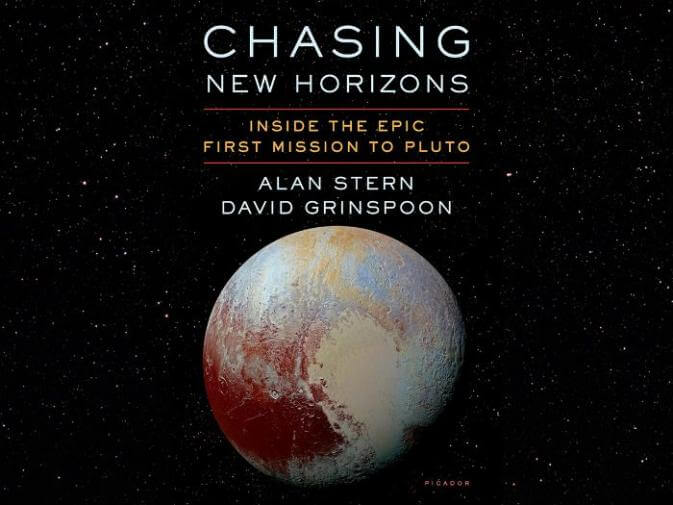

I sat down with Dr. David Grinspoon, author of the new book Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto, to discuss some of the stories that shed light on NASA's epic first mission to Pluto.

Sabrina Stierwalt: You are obviously a science communicator and an author, but you are also an astrobiologist, an advisor on space exploration strategy to NASA, a chair at the Library of Congress, and you’ve written about Venus and about aliens…so what made you decide to write about the New Horizons mission to Pluto?

David Grinspoon: Well, I love stories of exploration and I’ve been in love with space exploration my whole life. In addition to my own involvement in several planetary missions, I try to be as good a storyteller as I can. And I’m attracted to this story because this mission, New Horizons, is an incredible story. It’s a bunch of young dreamers who decided in 1989 that they wanted to send a mission to Pluto and were told that that was not a good idea, that it would never happen, it’s too far away and too expensive, and not important enough. And they didn’t let go of this idea. They were stymied in so many different ways and experienced so many setbacks. Then 26 years later they succeeded in sending this mission to Pluto. And then Pluto, of course, turned out to be extraordinary in terms of its scientific interest and its beauty and complexity and surprised us in so many ways.

So this story I think is emblematic of modern space exploration. It really shows you how it works. There are a lot of books that tell you what we discovered, but this one really tells you how it happens, how a mission goes from just an idea some people have to something that years later is fully realized. There’s a lot of detail in how that happens that people don’t know. This mission had it all—everything that could go wrong did go wrong and yet they persevered.

The other thing was that I had the opportunity to coauthor this book with Alan Stern who is one of these people in 1989—as a kid he was 30 years old just out of grad school—and he said I want to send a mission to Pluto and he was told no. He didn’t take no for an answer and now he’s the leader of that mission. He had all the stories of how this worked, and I worked with him to bring out those stories and construct this into a narrative where people can understand what it really takes to send a mission so far away and have it succeed.

SS: Well, and to give a sense of how far away it really is, New Horizons was launched in 2006, and didn’t make it to fly by until 2015 when it got our most detailed image ever taken of Pluto. So, that adds up to a nine-and-a-half year wait from spacecraft launch to fly by. That’s like preparing a pie—one with ingredients that cost you several hundred million dollars—and carefully placing it in the oven, only to know that you can’t enjoy your result for another nine and a half years.

That seems like such an incredibly long time to wait, but it’s really just the top tier of this cake. You alluded to the decades even before launch—I know you were involved in some parts of that process but what was your favorite part of that time to write about or to talk to Alan Stern about?

DG: I’m glad you mention that because people think, wow nine years, that’s a long project but actually there were decades before launch. It’s a really long project. And it’s not just a matter of waiting for the cake to come out of the oven during all that time. The team was busy during those nine years. There was so much planning and working with the spacecraft and ironing out problems with the spacecraft and detailed planning of the Pluto encounter. There was a Jupiter encounter on the way to Pluto which was both challenging and scientifically exciting. For the people involved in the mission, they weren’t just waiting for the dinger on the oven to go off.

For my favorite part, it’s hard to say. The moment of launch was just so exhilarating. I was there with a bunch of the members of the science team who were my old friends. Seeing Alan and all these people go through that after all these years of planning and then the anticipation that starts at that moment. It’s an anxious moment because rockets do blow up. Things can go horribly wrong. So it’s just this one moment where all these dreams from all these years in the past, all this work in the past, and all these dreams of the future are crystalized in this very powerful machine that is sitting there on the launch pad steaming, counting down, and then the countdown gets aborted because something goes wrong. You have to wait til the next day. So there’s all this built up anticipation and anxiety. And then there’s this very cathartic moment when it lights up and rumbles and streaks into the sky. It’s very emotional.

So that’s one of my favorite moments, the launch itself but then of course you can’t beat the actual arrival at Pluto, the way Pluto looked itself and the look on the faces of the team members and of the gathered public there seeing this wonder world revealed.

SS: I will back you up on the emotions. I just watched the TESS launch the other day with a group of astronomers and there was more than one face that was a little teary.

DG: Oh yeah! You think of maybe the cliché of engineers and scientists as these people who are not the most emotionally in touch people. I don’t think it’s an accurate cliché, but it’s this picture we have. But there are plenty of tears and heartfelt hugs and extreme partying into the night afterward. These people have been so pent up and then it works and it’s on its way...that really is a time to party. That’s another moment—those parties after launch and after approval when they discover they were going to get to do this mission, the parties after the encounter itself with Pluto—just the celebratory aspect after all the incredibly hard work after so many years and all the anxious sleepless part of the mission. Then when you are with these people and they are just enjoying the success, those are great moments as well.

SS: I can imagine. Your book is based on these conversations you’ve had with Alan Stern and his perspective as the lead scientist. But you also mention many smaller players that were just so key in making this mission happen. I’m thinking of Senator Barbara Mikulski and all that she did. Can you give us an example of a minor player that you enjoyed writing about or played a key role?

DG: As you mentioned, the core material for this were the conversations I had with Alan. For about a year and a half, we spoke every Saturday and I got really good material and wrote the first drafts of that. Then Alan and I wrote and rewrote them together and then there’s a lot of his first person quotes interjected into that.

But there are also a lot of other characters in this as well. It wasn’t just Alan’s story. I interviewed a number of other people that were involved. There are a lot of characters. I am glad you mentioned Barbara Mikulski because she’s a relatively unsung hero of this mission. It was on its deathbed several times where it got canceled by Congress or canceled by NASA multiple times, and Senator Mikulski came to its rescue. She was a supporter of this mission. She several times stepped in and said to NASA, "You can’t just cancel this. We’ve put too much into it," and kind of rescued it.

There are a number of members of the science team and the engineering teams who are real characters that I enjoyed talking to a lot. One of the key people is a scientist named Leslie Young who was Alan’s deputy project scientist through much of the mission. She was just key in planning the encounter, the very detailed planning of how all of the different instruments are going to work in sequence. It’s kind of like choreographing a dance. You have all these parts and they all have to do their thing at just the right moment in a way that doesn’t impede the other parts. It’s a very complex planning process. Leslie was sort of the czar of planning. But she’s also quite a character. She has this really kind of impish sense of humor and this very indefatigable spirit. There were several times when Alan would worry that Leslie was working too hard and staying up too late when they were working on this. And Leslie’s rallying cry, she would always just say “Whatever it takes, Alan, whatever it takes.” That was one thing that she said that then became a mantra for the mission, Leslie’s phrase “Whatever it takes”.

We even named part of the book that because that was just so emblematic of the attitude that was necessary for people to overcome the hurdles to allow this to happen.

SS: I love it. Am I remembering correctly that she’s pictured with Brian May in the book?

DG: Yes! And that was really fun too. There were celebrities who showed up and participated in the encounter. And Brian May, he’s the guitarist for Queen.

SS: And he has a PhD in astrophysics!

DG: Yeah, exactly, so he’s not just any celebrity. He actually joined the team and had interesting scientific discussions and he contributed some of his own stereo—he’s very interested in stereo imaging—he made some cool stereo renderings of Pluto. He got involved. He wasn’t just a sort of celebrity tourist. But it was really fun for some of these science team members like Leslie and the others to suddenly, in addition to exploring a new planet, they found themselves hanging out with Brian May.

SS: So one of the main things I think we’ve learned from New Horizons on the science side is that Pluto is not just this cold rock out in space. It’s actually a very complex planet with icy methane-snow capped mountains and frozen lakes of liquid nitrogen…Do you have a favorite Pluto fact that we now know thanks to this mission into our outer solar system?

DG: Every time we explore a new realm of the solar system, we’re surprised—maybe we shouldn’t be anymore because our assumptions prove to be wrong. And in particular when we explore the distant places in the outer solar system we expect them to be dead and then they’re alive geologically. The moons of Jupiter we thought would just be these battered ice balls. And in fact, Io is the most volcanically active place in the solar system and Europa is this cracked surface with an ocean underneath. Well the same thing happened when we got to Neptune and we saw how amazing Triton was.

And we shouldn’t have been surprised because we finally make it to Pluto and some people thought it might just be a battered ice ball when in fact it’s one of the most active planets there is. It’s just such a vibrant place. We have this saying “Pluto is the new Mars” that people started saying on that science team because it’s got such a range of features and such a complex surface. It’s got some very young, very active surfaces and other areas that are ancient and old.

So it’s really the complexity and dynamism of Pluto—that it’s an active world. If there’s one fact, if I had to distill it to one fact, it’s simply the fact that small worlds that far from the Sun are not dead. They are active. In particular, that on Pluto, these seas of nitrogen ice...who knew that you could have a planet that has deep layers of nitrogen ice that are moving? They’re convecting. It’s like boiling water—not that fast, but on a slow time scale—it’s clearly over turning and roiling and sort of bubbling up, this sea of solid convecting nitrogen. So to me, the fact that you can have a churning nitrogen sea on a world 4 billion miles from the Sun, that is an amazing fact that we learned from exploring Pluto with New Horizons.

SS: Yeah, it’s so exciting. Pluto is the new Mars! I love it. So, if you could pick, where should we explore next? Should we go back to Pluto and learn more? Should we venture beyond? Where should we go next?

DG: That’s such a hard question! Because if I ran the world, we would increase the planetary exploration budget by one or two orders of magnitude and we would have many spacecraft going to many places at once. If I have to pick just one mission, it’s so unfair. There are so many places I want to go. But certainly what we’ve learned from Pluto tells us that we have to go back. We need another mission. One isn’t enough.

Because, for instance, there’s the side of Pluto that New Horizons didn’t pass close by, that we saw from a distance on approach because Pluto rotates over 6.4 days. So there’s the far side of Pluto that we have sort of blurry pictures of that also looks sort of interesting and we only have vague ideas of what’s there.

And then the encounter side where we did get the close up pictures is so interesting that we have to see the rest of it. There are ongoing processes that we have to monitor. It’s an interesting enough place to be worthy of a return visit and probably a visit with an orbiter or maybe even a lander, something that sticks around and is not just a fly by that rushes through and takes some data.

So I’m not going to let you pin me down to one mission, but I am going to say among the plans of our exploration over the next few decades, a return to Pluto is very, very high on the priority list.

SS: Well, thank you. And thank you for talking to us about Chasing New Horizons

DG: Sure. I’m really glad to talk with you and I’m so excited to have the book coming out so that other people can learn of this amazing story that I learned so much about when Alan and I were writing the book together.

Image courtesy of New Horizons and nasa.gov

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar