The word “Ides,” as in “Ides of March,” denotes a single and singular day. But is the word itself singular or plural?

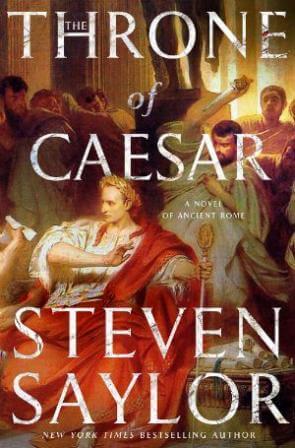

Far from being an ”idle” query, this question posed a real-world publishing conundrum for me recently. I write novels about ancient Rome. The latest, “The Throne of Caesar” (in bookstores on the Ides of March, incidentally), is a thriller centered on the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. Even readers with only a passing interest in the ancient world know the date of that event, the most famous murder in history: the Ides of March, which falls—or fall?—on the 15th of that month.

“Beware the Ides of March,” says the soothsayer in Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” The Roman dictator dismisses the warning as the muttering of a mere dreamer. On the day itself, as Caesar approaches his fateful meeting with the Roman Senate, the soothsayer reappears. Says Caesar to the soothsayer, wryly, “The Ides of March are come.” To which the soothsayer replies, fretfully, “Ay, Caesar; but not gone.”

Wait a minute—“The Ides of March are come”? Not is? Is “Ides” a plural noun? And if so, the plural of what? A single “Ide”?

Straightening out that verbal wrinkle mattered acutely to me some months ago when I was asked to give final approval to the book jacket for “The Throne of Caesar.” Rereading the jacket copy for the umpteenth time, I suddenly noticed that “Ides” occurred in two different places—and was treated as plural in one and singular in the other.

Jacket copy began: “It’s 44 B.C. and the Ides of March approach.” Some paragraphs later, jacket copy ended: “The Ides of March is fast approaching and at least one murder is inevitable.” Until that moment, no one had noticed the discrepancy—and this was the last day to make changes.

It then occurred to me, with a chill, that I might have used “Ides” as both plural and singular in the text of the novel. Uh-oh!

But a quick search revealed that while “Ides” occurred numerous times in the novel, in only three cases was the word accompanied by a verb that had to be either singular or plural, and in all three cases, without thinking about it, I had chosen plural. (“The Ides haven’t yet passed,” says a character.)

At least the novel was consistent—and surely the book jacket should agree with the novel. Thus the first sentence of the jacket copy was left alone while the last was changed to read, “The Ides of March are fast approaching and at least one murder is inevitable.”

In the meantime I had consulted more than one dictionary. Most (without explanation) assert that a verb used with “Ides” can be either singular or plural. Philologist friends informed me that the original Latin word, Idus, is in all cases plural. Tipping the scale was the fact that Shakespeare used “Ides” as plural, and if “The Ides of March are come” was good enough for Shakespeare, then surely it was good enough for me.

But why is “Ides” plural, and what does the word actually mean?

A (mercifully brief) lesson about the Roman calendar: each month had three nodal points—Kalends, Nones, and Ides—from which the days where reckoned backward. The Kalends fell on the first, the Ides on the thirteenth or fifteenth (depending on the month), and the Nones eight days before the Ides. All very confusing to us, though it must have seemed perfectly natural to the Romans, since their calendar had been handed down through countless generations.

Modern scholars speculate that Kalends, Nones, and Ides had something to do with the crescent, first-quarter, and full moon respectively. But what did the plural Latin word Idus mean?

Did I mention that the Roman calendar, and the words that went with it, had been handed down for countless generations? People tend to forget a lot over the centuries. By the time the Romans started reflecting on their long history and recounting the origins of this and that, including Idus, the meaning of the word had been forgotten. Ancient scholars could only speculate.

A canvass of the ancient sources provides no solution as to where the Latin word Idus came from, or why it was plural.

Our oldest Roman source is Varro’s On the Latin Language, dating from the first century B.C. Varro thought Idus might have come down from an even earlier civilization, the Etruscans, who, according to Varro, called that day of the month Itus. (It was a Roman commonplace to assign Etruscan origins to things too far back to recall; things Etruscan had the hazy glamour of antiquity.) But Varro gave no definition for either the Latin or the Etruscan word.

The query pops up again in Plutarch’s Roman Questions, written in Greek in the first or second century A.D. Plutarch says the Romans “name the Ides as they do…because of the beauty and form [Greek eidos] of the full-orbed moon.” So the words “Ides” and “idol” would have a common origin—but the idea of Roman calendar names stemming from Greek origins seems quite unlikely.

Writing much later—in the fifth century A.D.—Macrobius in his Staturnalia repeated Varro’s speculation that the word was Etruscan in origin, and added that this Etruscan word meant something like “Jupiter’s guarantee,” since on the day of the full moon light was granted to mortals not only by day but also by night. Clearly unconvinced of this explanation himself, Macrobius listed a number of other etymologies, “all fanciful” according to his 20th-century Loeb translator.

So, a canvass of the ancient sources provides no solution as to where the Latin word Idus came from, or why it was plural. (I won’t discuss here why some of us choose to capitalize Ides, Nones, and Kalends, and others do not, or the equally obscure origins and meanings of Nones and Kalends.)

Idus was plural to the Romans, and “Ides” was plural to Shakespeare. Thus (and perhaps because an -s ending makes many words plural in English) to me it feels right to say, “The Ides of March approach.” “The Ides of March is a day to beware,” sounds sweet to my ear as well, perhaps because “Ides of March” constitutes a single thing, despite the plurality of one component. But to me it seems jarring and downright displeasing to say, “The Ides of March are my birthday,” since the verb equating “Ides” and “birthday” agrees with one but not with both.

My advice, as a professional novelist: Always be consistent within a given text, and simply avoid any awkward-sounding construction. And by all means do not beware the Ides of March. Celebrate the day instead—perhaps with a visit to your local bookstore.

Image of The Death of Julius Caesar © Vincenzo Camuccini

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar