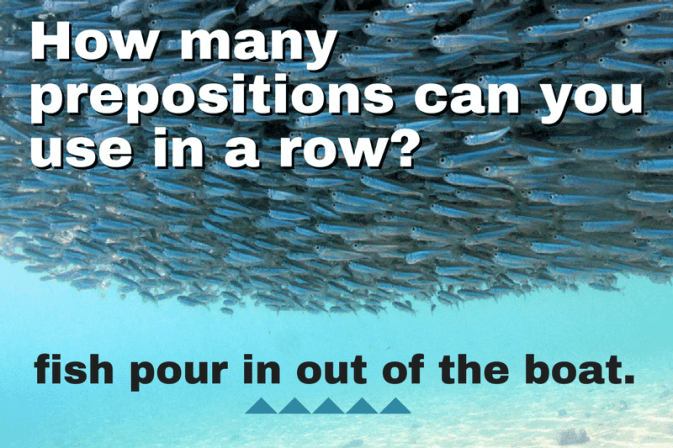

A listener named Morgan wrote in with a question about prepositions. In the novel “Cannery Row,” Steinbeck writes, “silver rivers of fish pour in out of the boats.” Morgan asks, how can we have “in out of”—three prepositions strung together in a row?

The trick to answering this question is to reframe the question. What if we aren’t looking at three prepositions in a row in this case? Then you can ask, “What kind of words are ‘in,’ ‘out,’ and ‘of’ in Steinbeck’s sentence?”

Although people often think of “in,” “out,” and “of” as prepositions, you can’t tell whether a word is a preposition (or any other kind of word) just by looking at it. To classify a word, it helps to know its grammatical role, its function in relationship to other words around it. And even then experts sometimes disagree.

Let’s start with a simple example. Consider the word “dog.” It morphs from noun to adjective to verb as you go from petting a dog to buying dog food to dogging it.

So what kind of words are “in,” “out,” and “of” in the phrase “pour in out of the boats”? We can say that “in” is a verb particle, and “out of” is a two-word preposition.

How so? Let’s step back and clarify the differences between three types of words that can be hard to tell apart: prepositions, verb particles, and adverbs.

What’s a Preposition?

A simple preposition is a word that appears immediately before—in pre-position to—an object (a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun). In other words, prepositions are “reliable signals that a noun is coming.” (1) A preposition connects its object (such as a noun) to some other element in the sentence.

Take the sentence “Squiggly hopped into the boat.” Here, the simple preposition “into” connects the noun “boat” to the verb “hopped.” We say that the prepositional phrase “into the boat” modifies the verb “hopped.”

A complex preposition, also called a phrasal preposition, is a preposition made up of multiple words. English speakers use complex prepositions all the time. Examples include “according to,” “along with,” “apart from,” “as for,” “because of,” “far from,” and “up against.”

So when fish pour in out of boats, they do so with the help of the phrasal preposition “out of.”

What’s a Verb Particle?

Any fish that find themselves pouring in do so by virtue of a phrasal verb. Just like a phrasal preposition, a phrasal verb (such as “pour in”) is a verb made up of multiple words. Each phrasal verb has a main verb (such as “pour”) and one or more small following words (such as “in”)—that work together to convey a single idiomatic meaning.

The phrasal verb “pour in” has the idiomatic meaning “flow rapidly in a steady stream.”

People often describe phrasal verbs as including a main verb plus one or more “prepositions.” The problem is that thinking of a word as a preposition in cases where it’s not behaving like a typical preposition can be confusing. That kind of confusion is exactly what Morgan experienced in contemplating Steinbeck’s sentence. If you want to avoid the confusion, you can call these words particles instead of prepositions when they’re part of a verb.

A phrasal verb creates meaning as a unit even if the main verb is separated from its particle or particles. For example, in the sentence “The student took the idea in,” even though “took” and “in” aren’t next to each other, the verb is “took in,” meaning “absorbed.”

English has thousands of phrasal verbs. Some have multiple meanings. For example, “to check out” might mean “to look at” (“Check out that elephant”), or it might mean “to go to a cashier” (“Here’s my credit card; I’m ready to check out"), or it might mean “to exit mentally” (“I’m going to put on Netflix and check out tonight”). “Put on” might mean “don clothes,” “josh a person,” “apply makeup,” or “play recorded music.”

The website UsingEnglish.com offers a quiz that contains some 2,000 phrasal verbs—a mere sampling—based on 171 main verbs. In this quiz, the main verb “get” alone spawns 167 phrasal verbs like these: “get back,” “get ahead of,” “get along with,” and “get over.”

You probably use phrasal verbs all the time. They give our language color and make it endearingly flexible—even as they make it maddening to learn.

What’s an Adverb?

Words like “in,” “out,” and “of,” which sometimes act as prepositions and other times act as verb particles, may even take a notion to act as adverbs. An adverb is a word that modifies a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. Adverbs commonly tell when, where, or how something happens.

For example, although the word “down” often serves as a preposition or a verb particle, it serves as neither in the sentence “The tired dockworker sat down.” Here, “down” is not a preposition (since it has no object), and it’s not a verb particle (since the verb has no idiomatic meaning). “Down” simply describes the manner of the sitting. In this case, “down” is an adverb.

Preposition, Verb Particle, or Adverb: The Quick and Dirty Tip

If you aren’t sure whether a word is acting as a preposition, a verb particle, or an adverb, ask yourself if the verb’s meaning is idiomatic or literal.

- If the word contributes to a verb’s idiomatic meaning—like the “in” in “pour in”— you can call it a verb particle.

- If the word’s meaning is literal—for example, if you were to talk about pulling in a net, where the “in” indicates the direction you’re pulling that net—you can call it a preposition …

- … unless there’s no object following the word—like the “in” in “Don’t fall in”—in which case you can call it an adverb.

In the three examples above (“pour in,” “pull in,” and “fall in”), the word “in” plays a different role each time: now a preposition, now a verb particle, now an adverb.

Let’s look at another example. This time we’ll stick with “ran out” each time.

Example 1—“Aardvark ran out of the boat.”

You can picture feet hitting the ground. Aardvark literally ran. In this case, “ran out” is not a phrasal verb because it’s not idiomatic. So it doesn’t make sense to call “out” a verb particle. Here, “out” is part of the phrasal preposition “out of” in the prepositional phrase “out of the boat.”

Example 2—“Aardvark ran out of boats.”

In this case, feet are not involved. “Ran out” is a phrasal verb, an idiom meaning “deplete the supply” of something. In this case, we can call “out” a verb particle.

Example 3—“Aardvark ran out.”

We’re back to a literal meaning of the verb. Since “ran out” is not idiomatic, it doesn’t make sense to call “out” a verb particle. And many people wouldn’t call it a preposition either because it doesn’t have a grammatical object. Aardvark simply ran out. Period. The word “out” indicates the direction or manner of the running. In that kind of sentence, you can call “out” an adverb.

Note that we’re choosing our words carefully here. Not everybody agrees on these categories. The point is, it’s sometimes helpful to classify words by their functions—which vary from sentence to sentence—rather than assigning them unchanging labels.

End a Sentence With Any Word You Like

In case you’re wondering about the so-called rule against ending a sentence with a preposition, wonder no more. This “rule” has been called a “durable superstition” (2), a “remnant of Latin grammar” (3), and (in another Grammar Girl episode) “one of the top ten grammar myths.” At least one editor reports seeing many a “tangled sentence due to reluctance to end a sentence with a preposition.”

The same goes for verb particles and adverbs.

So in your sentences, feel free to choose whichever words sound most natural to wrap up with.

Summary

This article’s title—How Many Prepositions Can You Use in a Row?—is a trick question. If you think you have two or more prepositions in a row, look closely. Words that we usually think of as prepositions—words like “in,” “out,” and “of”—may act as simple prepositions, parts of complex prepositions, verb particles, or adverbs.

Now that we’ve covered this topic’s ins and outs—oh yeah, “in” and “out” can be nouns, too—it’s time to pack it in and check out.

That segment was written by Marcia Riefer Johnston, author of “Word Up! How to Write Powerful Sentences and Paragraphs (And Everything You Build From Them).” Marcia blogs at Writing.Rocks.

References

(1) Klammer, Thomas P., Schulz, Muriel R., and Della Volpe, Angela. Analyzing English Grammar, fifth edition. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007, p. 117.

(2) Johnson, Edward D. “The Handbook of Good English: Revised and Updated” (New York: Facts On File, 1991), 386.

(3) Garner, Bryan A. Garner’s “Modern English Usage,” fourth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 723.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar