If you or someone you know has had appendicitis, the flu, herpes, hemophilia, leukemia, Parkinson’s disease, or even trouble digesting lactose, then your life is intertwined with that of Henrietta Lacks, the great-granddaughter of a slave born in southern Virginia. Hers is a story of revolution in medical science but also of a complicated link between medical research and the people that research is supposed to serve.

If you or someone you know has had appendicitis, the flu, herpes, hemophilia, leukemia, Parkinson’s disease, or even trouble digesting lactose, then your life is intertwined with that of Henrietta Lacks, the great-granddaughter of a slave born in southern Virginia. Hers is a story of revolution in medical science but also of a complicated link between medical research and the people that research is supposed to serve.

Henrietta Lacks grew up in rural Virginia where she lived and worked as a tobacco farmer on her family farm. She later moved to Baltimore with her husband who was pursuing a job in the steel industry. Together they had five children: Lawrence, Elsie, Sonny, Deborah, and Zakariyya.

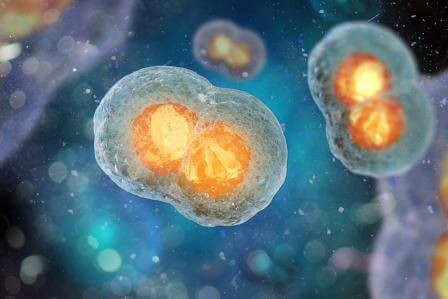

The HeLa Cell Line

In January of 1951, soon after the birth of her youngest child, Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital with uterine pain and bleeding. The doctors found a hard mass on her cervix and removed a small piece of the cancerous tissue for testing, according to standard practice, in the tissue lab of Dr. George Gey.

But unlike other cancer cells, her cells did not die within a few days. Instead, they doubled their numbers in 24 hours and continued to multiply. They were the only human cells known to grow outside of the body. Researchers were looking at an unlimited supply of human cells that could be used for any sort of testing without fear of their destruction, since there were always more cells to be tested. Her cell line was given the nick name “HeLa,” short for, of course, Henrietta Lacks.

Her cells have been used to study viruses like testing the safety and efficacy of the live polio vaccine and cancer drugs. Gene mapping, chemotherapy studies, and the development of in vitro fertilization techniques have all relied on HeLa cells. They’ve been used to study the long-term effects of radiation and even sent up into space to see how human cells adapt to life in microgravity. Her cells have been used in studies of appendicitis, the flu, herpes, hemophilia, leukemia, Parkinson’s disease, and lactose intolerance. Cosmetic companies, pharmaceutical companies, and even the military have used Henrietta’s cells for their own tests.

Millions of Henrietta’s cells live on in cell culture labs across the world. They have now lived outside of her body longer than they did within it. One estimate suggests that if you place all of her still existing cells end-to-end, they would wrap around the Earth at least three times, stretching more than 350 million feet .

The Lacks Family

During her treatment and upon her death from aggressive cervical cancer on October 4th, 1951, more of Henrietta’s cells were harvested by her doctors without her or her family’s permission. Nowadays, the origins of human cells used in lab testing are kept anonymous, but that was not a careful, standard practice in the 1950s. However, Henrietta’s doctors did use fake donor names like Helen Lane or Helen Larsen to confuse the source of their invaluable cell line.

HeLa cells were the first human biological materials ever bought and sold and have resulted in millions, if not billions, of dollars in profits. But Henrietta’s family did not see these profits. In fact, they were not even aware that their mother and grandmother’s cells were immortalized in laboratories all over the world until 25 years later. There are even stories of scientists doing research on her children and telling them it was to see if they had the same cancer as their mother, when in reality they were trying to learn more about her cells.

In the mid 1970s, researchers began to realize that Henrietta’s cells were such an immortal force that they could hitch a ride on dust particles in the air or the unwashed hands of researchers and contaminate other cell cultures in the lab. After significant contamination, one lab reached out to the Lacks family in trying to sort out which cultures were HeLa and which were not. With that communication, the incredibly important contributions that Henrietta’s cells had continued to make began to unfold for the Lacks family.

The debt we owe to Henrietta Lacks and her family for our understanding of the inner workings of our cells and of certain diseases is likely a debt that can never be repaid.

More people began to know Henrietta Lacks’s story when it was finally told in 2010 by science writer Rebecca Skloot in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, along with support from Deborah Lacks, Henrietta’s youngest daughter. In 2017, Oprah Winfrey played Deborah Lacks in a film based on Skloot’s book.

However, not all of the family is happy with their portrayal or the portrayal of their mother in the book. They rightfully point out the incredible injustice in million-dollar profits based on their matriarch’s cell line while some of her family members remain without health insurance themselves.

Some of that debt is being repaid. Skloot started the Henrietta Lacks Foundation with some of her book royalties, and the foundation has paid for college tuition, surgeries, and dental work for some of the Lacks family. Now members of the Lacks family also have a voice in a working group at the National Institute of Health that reviews requests from researchers who want to use the HeLa cell line in their work. Lacks family members are also commonly invited to speak at conferences and outreach events.

But the debt we owe to Henrietta Lacks and her family for our understanding of the inner workings of our cells and of certain diseases is likely a debt that can never be repaid. Henrietta’s story is one that reminds us that it is important not to lose our touch with humanity even as we conduct research trying to save people’s lives.

Until next time, this is Sabrina Stierwalt with Everyday Einstein’s Quick and Dirty Tips for helping you make sense of science. You can become a fan of Everyday Einstein on Facebook or follow me on Twitter, where I’m @QDTeinstein. If you have a question that you’d like to see on a future episode, send me an email at everydayeinstein@quickanddirtytips.com.

Image courtesy of shutterstock.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar